Mind over matter? Another unanswerable questionInteresting times and debates over the last week, where we discussed the issue of nature vs. nurture. It stimulated a good response, and some divided opinion, though most will probably agree that truly great performances are the result of a combination of genetic potential meeting hard work. Few would suggest that great sporting performances are entirely the result of a genetic gift that requires no training, and very few (the hopeless romantics) would suggest that anyone can be successful, regardless of their "natural talent" (a loaded word, as I'm sure you've come to realise).

For our part, we

lean more towards the talent side of things when it comes to "physiologically-determined sports" (a made-up concept, I confess) like sprinting, cycling, distance running. In these sports, success without some cluster of genetic and hence physiological advantages is highly unlikely. In sports where technical skills are crucial (golf, cricket, possibly soccer to a lesser extent), training probably becomes more important.

Perhaps the best summary of all was provided by Jamie in his comment, in which he said:

"One thing I do know for certain is that talented athletes that don't work hard will be good but never excellent, and hard workers with little talent the same".Well put.

A new topic - related, but no less answerableAn extension of that debate, and one which has little hope for an answer, is the

debate around whether mind or matter is the crucial determinant of success? For example, here's a hypothetical situation to consider: There are thousands of long distance runners around the world with the capacity to run a 10km in under 29 minutes (half of them probably reside in East Africa). However (and I'm using round numbers here), of those 1,000, perhaps 250 can dip under 28 minutes, and only another 50 can go under 27:30. Then you get the "sharp end of the sword", where perhaps 10 men have the ability to break 27 minutes, and only one with the ability to run under 26:20.

The question is this:

Is the difference between this man (Kenenisa Bekele) and the other 9/ 249/ 999, a physiological or a mental one?Take the same question and apply it to a sport where the opinion might be easier to express. Is the difference between Tiger Woods and the other professional golfers a technical one, produced as a result of physiology, or is it psychological? (which would also express itself as a measurable technical output in the golf swing, incidentally)

And, perhaps most importantly, should we even care? Can we even care, given how interlinked these aspects are - psychology determines the training attitude, training determines the technical parameters of the swing or the physiological abilities of the athlete, and that in turn feeds back to the mental and psychological state of the athlete! All this of course, happens within the framework of an athlete who we assume has the natural "predisposition" to succeed in the sport (we're not talking about an endomorph trying to crack 27-minutes here)

So it may well be a moot question. But it's one worth considering, especially for the endurance sports, which is obviously our focus. So herewith begins the debate on mind over matter!

A little bit of both, a lot of one or the other?Perhaps as you read the hypothetical and discussion above, you've already dismissed this particular argument as irrelevant, for the answer is so obvious to you that it's not worth discussing. And to a certain extent, I agree. It certainly does seem obvious that both are required, and that any athlete who lacks either the physiological ability (as a result of genetics or training insufficiency, doesn't really matter) or the mental toughness (for want of a better word) is destined to underachieve.

So let me

open the debate with our conclusion, courtesy Jamie, but with edits:

One thing I do know for certain is that physiologically-gifted athletes who lack mental toughness and capacity will be good but never excellent. And athletes with mental capacity off the charts who lack physiological 'hardware' will be the same.

Now, having said that, I'll bet that you can once again come up with a few examples of cases that disprove my contention! For example, you may cite yourself as a case of an athlete who simply lacks the physiological tools to run a super-fast time, but you believe that you've achieved 99% of your potential thanks to your mental approach to training. A far more likely case is that you have colleagues or training partners who would be streets ahead if they could just "get their minds right".

So there is a case for every argument, and a counter-case to prove the counter-argument, such is the debate.

But a common question asked in this debate, one which I've heard a few times, is "What percentage of elite sports success is mental?" And people throw out the numbers. Some say 50-50, you need both equally. Others

reckon that it's 90-10 in favour of the mental - if you don't have the mind, the body will never follow. A famous golfer, I forget who, was quoted as saying that the most important distance in golf is the 6-inches between the ears.

That kind of thinking is what this series of posts is designed to challenge. Not because it's wrong, but just because it

represents such an over-simplified view of how the mind and the body interact. And I really do believe that if the coach and athlete can understand the interaction better, and appreciate how they form a positive feedback loop, then the value of training can be increased.

Some problems with oversimplificationThere are, to begin with, a couple of problems with this kind of oversimplification. The first is that the measurement of physiology is much easier than the measurement of mental strength (again, I hate that word, but I am sure you follow what I mean). This has a few consequences.

Firstly, it creates a situation where it's

relatively easy to attribute unexplained performance to mental strength. I've mentioned a few times on this site that sports science really has very few answers to the question of why one athlete will beat another one. We can measure VO2max, lactate thresholds, fibre types etc, but the outcome of races never tracks these measurements perfectly. In fact, in elite populations, the correlations is poor. So now enter the "mind", and you have an explanation. I don't buy it. I am more of the opinion that sports science is failing to measure things, either by not measuring them at all, or by measuring them in too low a resolution. That's not to say the mind isn't vital, it's just too easy to dismiss physiology because you can't find evidence. The

default seems to be to explain the unexplained by bringing in the unexplainable!Second, and on the other side of the coin, the fact that it's all but impossible to measure the mental aspect of sport means that

people often disregard it. This has the exact opposite effect in that mental aspects are dismissed and emphasis is placed on things like fitness, flexibility, speed - parameters that can be tracked. The difficulty around designing an intervention to improve this mental aspect of sport is a barrier, when one can easily design a programme to improve strength or speed, and measure it and report back to the head coach/physiologist on the progress.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the

two are interlinked so tightly that to debate them separately is, as I pointed out at the top, something of a doomed effort. The problem is that we see the achieving, winning athletes (like Lance Armstrong, let's say) and we see the athletes they beat (Jan Ullrich), and it's all to

easy to say that the difference between them was Lance's toughness, his attention to detail and his never-say-die attitude. Problem is, none of those have ever been measured, nor are they really measurable, and so they are

subject to human emotion, to propaganda and consequently, bias (by design or by accident).The same goes for Tiger Woods - the "Lore of Tiger" speaks of his legendary training routines, his attention to detail, his mental toughness. So we believe it because he wins. I am sure you can think of others - as soon as they win, we find reasons why they are winners, in hindsight. And we're right - these stories, the backgrounds, the history are integral to any athletes' success, and can't be discarded. However, we attribute success to them, which again, is a gross undersimplification. And we never control for the fact that he might be a more gifted athlete. And we

never ask the loser how tough he might have been, because we don't care - he lost, after all!

Apart from this, to suggest that one athlete beats another because of mental toughness can be incredibly disrespectful to the loser. Not always, because sometimes it is clear that an athlete loses because of some frailty in their mental armour. However, to suggest that Haile Gebrselassie beat Paul Tergat in five major 10,000 finals, including two Olympic Games, because he was tougher, is to say that Tergat didn't want to win. Unfortunately, this

debate is often simplified down to the age-old argument, heard in pubs and bars around the world: "They won because they wanted it more". Rubbish. Having lost four races, did Tergat not eventually start wanting to win? Did Jan Ullrich start the Tour with the idea that he'd be satisfied with second? It just seems so simple to attribute success and failure to a difference in desire. Even if you believe mental is everything, you have to appreciate that there is more to it than this!

So, hopefully, the problem is clear: We cannot control for the absence of half the variables - physiology does not exist separate from mental aspects. In fact, they feed each other, so that the athlete who has both will end up being physiologically superior and mentally tougher. In that respect, the argument is somewhat circular.

The role of the brain in performance - not mind over matter, but matter over matterHowever, before we get too philosophical here, let's just wrap up by saying where we are going with this.

About a year ago, I did a

series of posts on fatigue. These posts are well worth a read for the current posts, because they'll come up next time again.

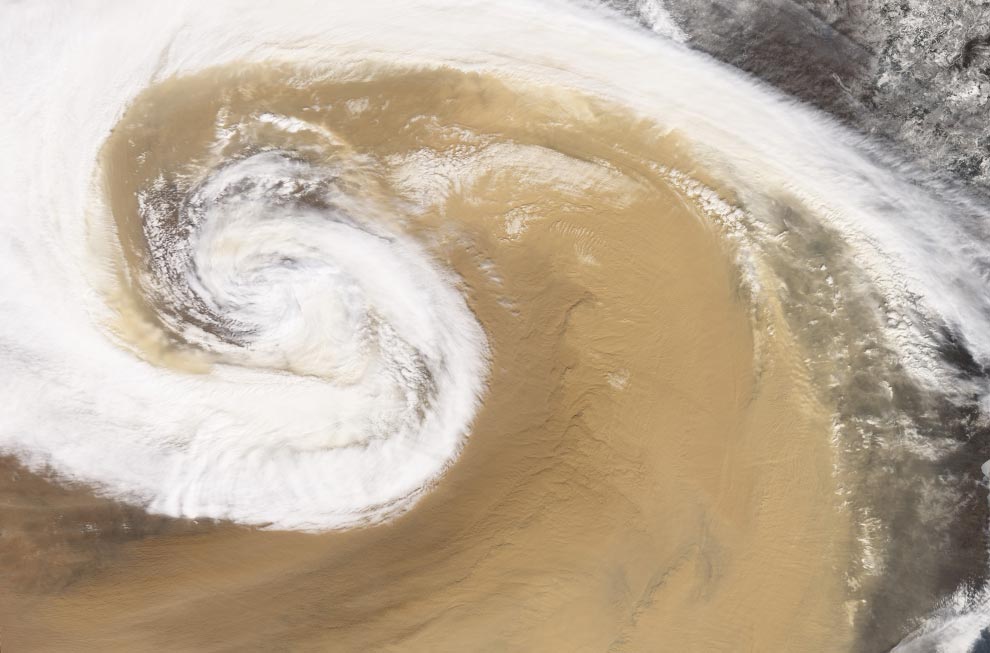

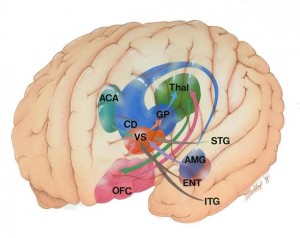

But the take-home conclusion from that series, is that fatigue (and ultimately, the limit to performance) is NOT a function of VO2max, muscles, lactate, glycogen, over-heating etc., but rather is a regulated process, where the brain collects all kinds of information from the body and then assimilates it into a perception of effort. The end result, which has been measured physiologically, is that the

brain controls how much muscle we activate, and slows us down IF it calculates that we are in danger.

For example, when you exercise on a hot day, you don't slow down because you are too hot. Rather, you

slow down because if you didn't, you would get too hot. The brain works out just what is possible and then regulates pace in order to achieve the best possible performance with the least possible risk.

Now, the obvious extension of this is that if your brain makes the decision, then you can "trick" the brain, or discipline it, into delaying that decision, which would allow you to run or ride faster before that point is reached. Instead of slowing down, you'll hang in there, guts it out, suffer through the pain, because your performance will be improved. It's classic mind over matter.

Unfortunately, this doesn't work, for much the same reason that

people are not very successful at committing suicide by holding their breath! It doesn't matter much how badly you want to go, your

physiology will win in the end.However, there is no doubt that

some people are able to get closer to this physiological limit than others. Perhaps, in the context of endurance sport, this is what we mean when we speak about "mental toughness" - the ability to approach that limit, either through desire, belief or any other complex collection of attributes and attitudes. Their brains regulate performance much more tightly than others, those who are "conservative" and finish the race with a much larger reserve. So therefore, we have a case of "matter over matter" - it's brain matter regulating body matter.

And since we're The Science of Sport, that's where the discussion kicks off next time - the physiology of performance, and the role of the brain in regulating our limits!

Ross

The Science of Sport Dr. Ross Tucker Dr. Jonathan Dugas